|

Shanghai prose and party queen

Mian Mian reflects the harsh realities of post-Mao material China in her

books about wretched love affairs, hard drugs,

promiscuous sex and suicide.

"My first time is brutal. The Doors are playing

on the

stereo. I can't understand the excitement on his

face.

I don't know my own needs. In his embrace, I am like

a sad silent cat. Sudden bleeding inside my body. I

go to the bathroom. A fussy face in the mirror.

He is

a stranger. We met in a bar. I don't know his name."

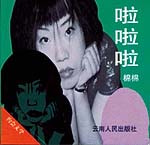

La, La, La--Mian Mian

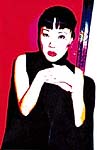

A huge, crackling neon sign

bolted

over the window bathes 29 year-old Shanghai

writer Mian

Mian in scarlet and sour green light. Skin

flushed and

sensuous one moment, anemic and lifeless the

next, she

lounges on the bed in a cheap Shanghai hotel

dragging

on one in an endless chain of cigarettes. Soon

she will

prowl the city's bars and nightclubs, seeking out

the

doomed and the damned that populate her roman a clef

prose. Prostitutes, junkies, strippers and club

kids.

Gangsters, punks, groupies and pimps--all are

not-so-fair

game for this nocturnal chronicler of China's seedy

underbelly. Typifying a new generation of writers

who

are shaking off the Party's creative shackles and

spurring

Chinese fiction into unexplored territory, Mian

Mian's

milieu is marked by wretched love affairs, hard

drugs,

promiscuous sex and suicide. Her own tale is one of

personal liberation, excess and redemption.

"Writing is much more than my

life,"

the vivacious, reformed heroin addict says, flashing

a tight smile. Her kind, curious eyes are framed by

a harsh, geometric bob, and her famished frame is

clad

head-to-toe in black. "Writing saved my life."

Mian Mian's first, confessional book of

cosmetically-fictionalized

short stories La, La, La was published in Hong Kong

in 1997. Three fresh volumes--Acid Lover, Every Good

Kid Deserves Candy and Nine Objects of

Desire--are about

to be released to China's reading masses.

"Mian Mian is the most original voice of

fin-de-siecle

Chinese fiction," says avant-garde Shanghai literary

critic Zhu Dake. "She doesn't lament her, and

China's,

harrowing past. She chronicles her life, and the

lives

of young people on society's fringes, with an

analytic

eye."

Mian Mian's writing life began at the age of 17,

when

a Shanghai classmate slit her wrists. "Everyone

in China

knows someone who has committed suicide," she

says with

the flick of a chalky hand. According to the

World Health

Organization (WHO), China's female suicide rate

is the

world's highest--21 percent of the world's women

live

in China, yet 56 percent of those who commit suicide

worldwide are Chinese. Even so, the tragedy was a

turning

point. Explaining her first attempt at writing, she

adds: "Life was so dark back then. I don't know why,

I just felt I had to get it down. I needed to write

the pain out of me."

Like so many restless youth of her post-Mao

generation,

she fled south to the urban anonymity of

Shenzhen. Seduced

by the bright lights and free market vitality,

she embraced

a debauched life of late nights, marijuana, booze

and

rock music. But harsh reality crashed the party when

she lost her virginity. "Basically, he raped me,"

she

says. "I thought: 'That's life.' I was young. It was

my first experience of men. I knew nothing else."

First

love also proved traumatic. After a few blissful

months

of much-needed stability, she was devastated to

discover

that her sweetheart, the singer in a band, was

sleeping

with her friend, a neighborhood prostitute. Self

esteem

in tatters, she bedded a procession of faceless men,

as recounted by La, La, La's feral narrator.

"I met a guitarist at one gig," Mian Mian says in

the

same detached tone as her fiction. "He was

beautiful,

totally irresponsible. We were with friends,

drinking

and smoking, talking about music, men and women, how

to give a good blow job. When the sun came up, he

said:

'Why don't we go to my place.' He was the best I've

ever had. Even better because he left town the next

day. I've never seen him since."

Mian Mian soon began using heroin--every day for

three

years. "I was sick," she says matter-of-factly.

Penniless

and ravaged by her addiction, Mian Mian limped back

to Shanghai at the end of 1994. Her

civil-engineer father

and Russian-teaching mother, tipped off by Mian

Mian's

best friend, found heroin in her bag and

committed her

to rehab. After a brief relapse when she bolted back

to Shenzhen, she finally went cold turkey at age 24.

"We grow up fast now," Mian Mian says, reflecting on

the wrenching generation gap that has emerged

from the

post-1989 materialist revolution in China. "China

was

so poor. Now, in the cities, there's money

everywhere.

Kids read foreign magazines, watch MTV, they are on

the Internet, they take ecstasy, ice, smack, and

they

sleep around."

Exhausted by her addiction, rehab, relapse and final

recovery, Mian Mian hid from the world in an

out-patient

clinic. "When I left the hospital, I could barely

speak,"

she recalls. "I didn't see a future for myself. I

wanted

to die." Moping in her darkened room, she watched

videos

and listened to Janis Joplin. Whenever she felt

strong

enough, she poured her torment onto paper. Two years

later, she had completed a short story, which she

submitted

to respected Literary World magazine (Xiaoshuo Jie).

The editor told her what she needed to hear: she had

talent, and a new lease on life.

"The most striking aspect of Mian Mian's writing is

that she places a high priority on personal

perception,"

explains Wang Hongtu, critic and senior lecturer in

Chinese literature at Shanghai's prestigious

Fudan University,

adding that her non-conformist approach

highlights the

increasing tolerance in China's cities of

alternative

lifestyles. "Writers of previous generations took a

more positivist approach to their work and society.

Writers who have grown up in the post-Mao,

materialist

Deng era are the first in China to stress the

individual's

needs over the collective." "I prefer simple, direct

language," explains Mian Mian, who types in the dark

and always at night. Holed up in a secluded villa

outside

Shanghai, she cranks up the house and techno

music that

inspires her, and completes a new piece every

four days

on average. "I tell it like it is, from real

experience.

I want to tell people that freedom is great, but

that

it can also be dangerous.

"I don't think of myself as a writer. I'm

troubled and

stupid like everyone else. I grew up on the streets.

I have friends who are dead, friends in jail,

friends

who are prostitutes, on drugs, drunk, married to

shitty

men. I write because I need to write, to make sense

of life. Honesty is everything to me."

Being a woman does not help. Mian Mian reports that

prudish censors are continually deflecting her

incisive

attacks on the jugular of male-dominated society. In

one of her stories, the narrator fantasizes about

making

love to a stranger.

"They changed that to: 'Seeing him makes me feel

sad,'"

Mian Mian scoffs. In another story, she used the

phrase:

'I'm your zero' intended to reflect a feeling of

emptiness.

"The publisher said: 'We can't have that. You're

a woman.

People will think you're talking about your 'hole'."

Similarly, the words 'I feel dry' were slashed.

"They're

crazy. I was talking about my head, not my body." To

maintain integrity, each of Mian Mian's four

books has

a different publisher. "They all want to pay me, to

package and market me. But I don't trust them. As it

is, I can argue or walk away. Once I have their

cash,

they can change whatever they want."

Mian Mian has recently been approached by foreign

publishers

eager to translate her work. To reach a wider

audience,

she plans a series of short works dissecting the

disfunctional

relationships between lonely expatriates and

Chinese.

Heroin, she asserts, is a ghost of her past. And

though

the pinprick of oblivion still exerts its

attraction,

that is where it will stay. These days, she

sticks to

the occasional social joint--the amnesiac effects of

ecstasy uncomfortably remind her of the steady diet

of tranquilizers she was force-fed while in drug

rehabilitation.

She still organizes parties, drinks to excess and

seduces

men. "Research!" she says with a staccato laugh. But

she also finds time to fine-tune Candy, her first

full-length

novel covering 11 "cruel" years in the life of a

young

Chinese couple. Once again, sex and drugs play major

roles, along with alcohol and insanity. Once

again it

will be semi-autobiographical. But Mian Mian insists

she has not yet stripped herself, or modern

China, completely

bare.

"My own life is far more extreme than the stories

I'm

writing now," she says dolefully. "I'm not quite

ready

to tell my complete story just yet." Mian Mian

shrinks

down into her black leather jacket, and the

oversized

garment accentuates her delicate features. Her eyes

betray a hint of vulnerability before she takes

another

drag off her cigarette and declares: "But I will

tell

my whole story eventually."

|