Chen Qingqing and her Work Forty

Years of Life and Art in Beijing

Most contemporary Chinese artists studied fine

art at a university. Chen Qingqing (pronounced ching-ching) studied

tractor driving at a ru ral cadre school and learned traditional medicine

as an apprentice to an octogenarian doctor. But four years ago she began

a new career as an artist creating installation works that have since

been exhibited in Vienna, Beijing and Bangkok. Last year she was the

first foreigner to be invited to join the Austrian Artists’ Association,

and her art continues to attract attention in China and abroad.

The 46-year-old artist was born in Beijing to

idealistic communist parents who both held high-ranking positions in

the Ministry of Culture. They were bookish intellectuals themselves,

but they actively discouraged Qingqing from studying arts or humanities

because, like parents everywhere, they felt that work in these fields

was unstable. Their fears proved all too real in their own cases: they

were removed from their jobs and persecuted during the (1966-1976) Cultural

Revolution. Some of Qingqing’s earliest memories are of being alone

at night in her family’s central Beijing courtyard, listening to

the shouts of Red Guards just outside the walls and expecting to receive

a less than civilized visit.

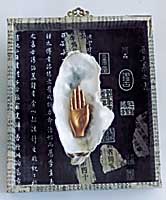

After several years abroad, she has returned

to life in the hutong. She lives and works in a small courtyard house

next to the “lake district” in central Beijing. She is currently

busy on a series of small installations entitled Black Memories. These

glass-topped black boxes resembling little museum cases are filled with

photographs, found objects and miscellanies like roses and rose stems,

slippers for bound feet, newspaper cuttings, miniature hands and ears

and extracts from Chinese medical texts. The arrangements are thought-provoking

even without any knowledge of the artist, but after Qingqing relates

the memories behind Black Memories, the small boxes seem to resonate

with real and imagined impressions of the recent history of Beijing,

which often parallels her own life story.

Qingqing is unusually tall and moves around

her small concrete-floored studio with the awkward elegance of a giraffe.

She has an innocent-looking smile of curiosity and is quick to laugh,

especially at the many absurdities of contemporary Beijing. She chuckles

at the current fashion among the capital’s Sino-foreign art clique

for greeting with a kiss on each cheek. Foreign habits like coffee and

kissing are so easily accepted in the capital today, but she remembers

when cheese was an oddity. Qingqing’s childhood home was in the

former diplomatic quarter in Chongwenmen, where there was a shop that

sold foreign foods. Qingqing’s mother told her that the smelly

white substance on sale was a “milk carrot.” To quote L.P.

Hartley, “the past is a different country,” and nowhere in

the world is this as evident as it is in Beijing.

Despite their status as high level cadres, Qingqing’s

parents never owned anything except for books—many, many books.

As the first head of the Xinhua News Agency, her father was given a

copy of every book published in the People’s Republic. Aside from

this massive library, every item in the Chen family house, down to the

smallest tea cup, was state-owned. This was communism in its heyday,

and the state provided everything you needed. But in 1966, all that

changed. Ironically, it was the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution

that forced Qingqing’s family out of their state-sponsored housing

and into a situation where they had to buy their own furniture. Qingqing’s

clearest memory of the start of the Cultural Revolution was a day in

1966 when her father instructed her and her two sisters to choose a

few books that they really liked and burn the rest for fear of being

criticized for owning “reactionary” texts. The 13 year-old

girl spent three whole days watching a pile of books burn to cinders

in the yard.

In 1969 Qingqing and her mother were sent to

a collective farm in rural Hubei. Qingqing was assigned to tractor driving

duty. It is easy to imagine her sitting high up on a noisy tractor like

a rosy-cheeked girl from a propaganda poster, except that the official

beatific smile is replaced by a mischievous grin that still charms today.

The girl-meets-tractor romance was brought to

a sudden halt by a stomach ailment that resulted in an emergency operation.

The operation took place on a rural farm with no modern facilities.

A hole was opened in Qingqing’s stomach, using only a local anesthetic

to kill the excruciating pain. When the doctor realized the condition

was more serious than it had appeared, another doctor was called and

general anesthetic administered, but the operation took an entire day

in primitive and unhygienic conditions. Qingqing remembers waking up

and seeing an apple on the table. Despite the pain in her stomach, she

ate the rare treat immediately.

Soon after this she returned to Beijing with

her mother who was seriously ill. Her mother died and she was left alone

in the capital to fend for herself. In 1971 she got a job in a factory

and then began to work in a clinic where she resumed the study of medicine

she had begun before her stay in the countryside. She learned about

Chinese and Western medicine at the clinic’s dispensary but was

eventually asked to leave her position because she had no formal medical

training. She continued her pharmaceutical apprenticeship with an old

man in her neighborhood. He was frail with age and unable to use his

hands, so Qingqing wrote prescriptions for him. As well as giving her

access to his extensive knowledge of traditional medicine and the theory

behind it, the old man taught Qingqing to read classical Chinese. In

an unhappy time when China was rejecting everything old as feudalistic

and primitive, she spent her days exploring the ancient philosophies

behind the practice of Chinese medicine.

Classical texts were not enough to help her

deal with the aftermath of the Cultural Revolution however. Her father

emerged from eight years as a political prisoner to find that his wife

had already died. He killed himself, leaving Qingqing completely on

her own to answer the existential questions that plagued (and still

plague) the generation who lost their childhood to the Cultural Revolution.

She learned English and German and became one

of Beijing’s first group of hipsters who listened to the Beatles

and read books like On the Road, obtained by well-placed friends from

special bookstores for government officials. “We had too many questions

and we couldn’t find the answers in Chinese culture,” she

says, recalling that time when even foreign clothes were exciting and

offered glimpses into an entirely different reality. Qingqing’s

sister was among the first group of mainland Chinese to emigrate to

the United States. She sent Qingqing a pair of blue jeans, an article

of clothing that still attracted a lot of attention in the homogeneously-clothed

China of the early reform era. Qingqing’s beatnik phase ended when

she got a job with Siemens, the German electric engineering multinational.

She earned an unimaginably high salary by local standards and began

a life of business trips and stays in expensive hotels.

“I kept thinking all the time. I wanted

to find a real life for myself, but I was trapped between two worlds,”

she says. “I didn’t quite fit into the foreign community,

but I was living a completely different life from my Chinese friends.”

This was the early 1980s. Qingqing’s well-paid job and passport

gave her some of the privileges experienced by the first generation

of Mainlanders to enjoy the benefits of Deng Xiaoping’s economic

reforms. After a long period of moving between Austria and Beijing,

Qingqing decided to reintegrate herself into the Chinese community by

opening a restaurant. Situated in western Beijing, “My Generation

Restaurant” (yidai ren canting) served up home cooking and Guizhou-style

hotpot. Qingqing’s idea was for the eatery to become a place where

her friends could meet and talk freely in a convivial atmosphere. These

days, every bar owner in Sanlitun says the same thing but in 1992, with

the exception of expensive hotel bars, there was nowhere to just hang

out. Qingqing ran the restaurant for almost two years. She found herself

in the strange underworld of urban Chinese restaurants, keeping the

company of corrupt policemen who expected to be fed for free, rowdy

drunk customers and waitresses from the countryside who would sometimes

be lured away by pimps.

There were some rewards though: Qingqing’s

friends did come round and hang out, and she was able to start what

was perhaps Beijing’s first unofficial women’s group. The

first meeting of the women’s salon discussed issues which the restaurateur

herself had raised in an essay about the dissolution of the family unit

in contemporary China. A group of women gathering together to discuss

what could be called “family values” is considered a harmless

enough activity in many places, but Beijing in the early 1990s was a

paranoid place and Qingqing’s second salon was stopped by the authorities.

Qingqing gave up the restaurant business and began to consider other

avenues for her creativity.

In 1995, she produced a series of artworks consisting

of installations made with ropes. In China,there is still no officially

recognized category of visual arts called “installations”

so the works were labelled soft sculptures instead. The pieces were

exhibited at a gallery in Beijing. They sold well and attracted a lot

of interest, and Qingqing finally realized what she wanted to do when

she grew up: make art. “I have good ideas, good eyes and a good

hand—not everybody has that,” she says, commenting on her

smooth arrival on the contemporary art scene.

Some of her most striking installations date

from this period. Particularly memorable are a series of works connected

with ideas of home and exile. Most were made between 1995 and 1998 when

Qingqing was deciding whether to emigrate to Austria. The installations

consist of spiky balls made of wire lit from within by warm yellow lights.

Like a dysfunctional home, they look cozy from afar, but are prickly

from up close. A work entitled On the Way is made up of a warmly-lit

spiky ball nested in a battered suitcase. Flight is a spiky ball impaled

on a broken umbrella. It suggests a flying object like the Sputnik satellite,

but also a bird or bat with broken wings.

Shuttling between Vienna and Beijing, Qingqing

began spending most of her time and energy on her art. Although she

has a good calligraphic hand and can paint, she prefers working on installations,

or materials art. “Traditional art in China is the art of mountains

and water,” she says, “but in Peking there are no mountains

and water. The kind of art I do is based on materials. Peking is developing

very fast and this means there are always a lot of interesting materials

to work with, materials that represent a more realistic, contemporary

Beijing.”

Her approach to visual art is both contemporary

and demotic. In 1997 she mounted a massive light installation inside

the upmarket Scitech Plaza on Jianguomenwai Street. Instead of the usual

suspects from the Beijing art clique, this work was seen by thousands

of ordinary people who came only to shop. The middle-class consumers

gawking at her work made her happy. “I can’t separate myself

from social life,” she explains. “Like fruit that needs roots

to nourish it, art needs relations with the people around it.”

Although some of her works are physically large,

they are understated. Installation art often intends to shock.

Qingqing’s work tends to be contemplative

and suggestive rather than imposing or offensive. Her current exhibition

at Red Gate gallery consists mostly of clothes made from hemp fiber.

On some pieces dried roses and leaves are affixed to the material—spiky

symbols of a fading idea of femininity. Other works wear their lonely

hearts on their sleeves: the hemp is covered in “seeking spouses”

advertisements in German, Chinese and English.

There is a balance between natural and synthetic,

hard and soft, masculine and feminine. Soft light contrasts with hard

wire. Natural hemp fibers and roses are set against the urban anonymity

implied by lonely hearts advertisements. The Black Memories boxes contain

objects of nature that have been tamed, twisted or transformed by culture

and industry. There are miniature shoes worn by women with bound feet,

plastic body parts, dried gourds and seed pods, baby bottle teats, parts

of musical instruments, broken bracelets, sea-shells collected on her

transcontinental travels and Chinese medical texts about herbs, acupuncture

and the manipulation of natural forces.

Qingqing as an artist succeeds in balancing

recollection of the past with contemplation of the present. Although

her installations use the most contemporary materials, they have an

equilibrium suggestive of ancient Chinese theories of harmony. Qingqing

has pursued a unique path to a career as an artist. A lifetime of diverse

experience is starting to produce strange artistic fruit of increasing

relevance to citizens of Beijing and the world.

|